Forgotten in Life, Remembered in Death

Every night I come across something that makes me really sad or angry, but tonight it sparked my curiosity. While reviewing my usual ten lairs, I came across an entry for Jane Japp. As I looked into her history, I discovered she suffered from St Vitus’ Dance, also known as Sydenham’s chorea.

St Vitus’ Dance, or Sydenham’s chorea, is a neurological condition that typically develops in childhood following an infection caused by Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus — the same bacterium responsible for rheumatic fever. The hallmark of this condition is involuntary, rapid, and irregular movements of the arms, legs, and facial muscles. It affects girls more commonly than boys and usually appears between the ages of 5 and 15.

Today, St Vitus’ Dance is generally treated with a course of penicillin. However, in the late 1890s, Jane was admitted to the asylum system, where she remained until her death in 1900.

The Bairns Lair 183 & 306

It seemed like any other evening, with people liking comments on the FoHPC page, until at 8:30 pm Tom shared a little more about Baby Moses resting in Lair 306.

Her name was Martha, and she had a brother, Philip — someone we had no knowledge of until now. We were unaware of any other infants buried in the cemetery, as no other records mentioned babies.

But how quickly that changed with a click of a button and some data sorting.

Philip was found in Lair 183, with no indication in the records that he was a child apart from there being 3 persons in the lair

Both Martha and Peters mum is not buried with her children and we have no record of where she is, but I hope she knows we will look after her babies as best as we can

I want to share something I hope you’ll never have to know: how a heart can break and tears can flow endlessly. They lost their babies, you see — angels in their eyes. God chose to take their hand one day and lead them to the skies. But please, do not forget their child. They were a person too, and forever they will live inside of me and you.

So, please don’t ever say that time will heal their pain, because not even time can bring them back again. Just tell them they are happy in that land far above, snugged in an angel’s wings and wrapped in a mother’s love.

Robert Bell Lair 271

Robert Bell – Lair 271

Robert Bell was born around 1868 in Glasgow to Robert Bell, a blacksmith, and Elizabeth Bell (née Bell). He appears to have been part of a large family, with records showing at least six sisters — Jessie (b. 1864), Annie (b. 1866), Jane (b. 1870), Elizabeth (b. 1871), Margaret (b. 1874), and Agnes (b. 1883) — and one brother, James (b. 1876). Another brother may have died young, as he does not appear in census records.

Interestingly, the 1881 census also lists another James Bell, born in 1860, living at the family home. It’s possible he was an uncle to Robert, raised as a sibling — a common occurrence in extended households of the time.

Robert’s parents were married in 1863 in Bridgeton, Glasgow. Over the decades, the family moved several times within the Glasgow and Rutherglen area:

-

1871 – 366 London Road, Calton, Glasgow

-

1881 – 11 Green Wynd, Rutherglen

-

1891 – 31 Burnhill Street, Rutherglen

-

1901 & 1911 – 34 Mill Street, Rutherglen

By 1911, only Robert (aged 43) and his father (aged 68) were living at the Mill Street address. The 1915 Valuation Roll confirms Robert senior was still the tenant there.

Robert’s mother disappears from census records after 1891, suggesting she may have passed away sometime in the 1890s.

Robert lived with clear physical and cognitive disabilities. Census entries describe him as “not strong enough for work” (1881), “born paralysed in lower limbs” (1891), and “feeble-minded” (1901). Despite these challenges, he remained with his family throughout his life, possibly cared for by his father until the older man's death. It seems likely that Robert was admitted to Hartwood Hospital shortly after becoming alone or unsupported.

Robert died within Hartwood on 5 April 1918, and was laid to rest three days later on 8 April 1918, in Lair 271.

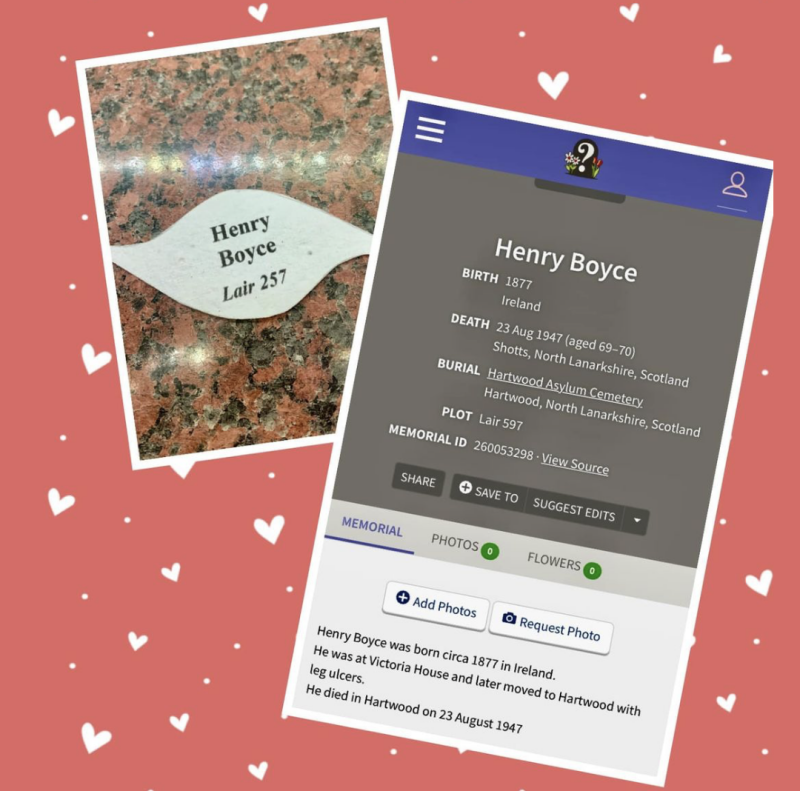

Henry Boyce Lair 257

Catherine Thomson Weir Lair 612

One of Only Seven Headstones. One Heartbreaking Story.

Once again, our hearts are broken as we uncover yet another powerful story among the 1,255 souls laid to rest at Hartwood. This time, the story comes through an email we received from Cathy and Darren Crerar in Australia—relatives of Catherine Thomson Crerar, one of the very few individuals in the cemetery to have a headstone. What they shared is both deeply moving and a poignant reminder of how mental health and silence shaped so many lives.

“Hiya, You can all be very proud of the work you are doing with the cemetery. We came across your group while Googling during COVID and were so excited to see the photos. We visited Hartwood in 2018 but sadly missed the cemetery—only to later discover that Darren’s great-grandmother, Catherine Thomson Crerar, is buried there in Lair 612 with a headstone.”

Catherine’s name also appears on the family memorial in Carnwath, but until recently, her story had remained largely unknown—even within her own family. There had been a long-standing belief that Catherine had died when her children were still young. In reality, she remained at Hartwood Hospital for many years. Darren’s grandfather, John Weir Crerar, Catherine’s youngest son, was told she had died when he was a boy. Tragically, he only learned the truth during a visit in 1950—just after she had passed away.

Cathy and Darren wondered who had placed the headstone, which bears only a simple tribute: “In Memory Of.” A follow-up email later confirmed that John and his brother Daniel—Catherine’s sons—were responsible. Her husband, Daniel, had passed away in 1946.

“We believe Catherine found some contentment in her situation and think she would have been very proud of her sons and all the following generations. Imagining her grave with snowdrops blooming is a comforting image.”

The family visited many of Catherine’s former homes on their 2018 journey, including:

-

Westsidewood, where she was born—now a stately home.

-

Cleugh Farm, Wilsontown, now operating as a B&B called The Bothy.

-

Newmains Cottage, Catherine’s last known home before her long stay at Hartwood. It still stands today and is now named Dippoolbank. The gardens there have been part of the Scottish Open Gardens scheme:

Dippoolbank Gardens

They’ve even considered purchasing something from Dippoolbank to plant in the gardens at Hartwood—an act of remembrance and connection across time and continents.

Catherine's hospital records were detailed at first, but like many patients of the era, the entries slowly faded away as the years passed. It’s believed she never returned home, but the family noted that in 1916, during WWI, her eldest son Daniel listed her—Catherine of Newmains Cottage—as his next of kin on his military records. A flicker of connection that remained, despite everything.

“It is important to talk freely and be open about our past and share the knowledge to understand and begin the healing where it is needed.”

We are so grateful to Cathy and Darren for sharing their family's story. Catherine’s headstone is a rare and silent witness to love, resilience, and remembrance. Her story, like so many others, deserved to be known—and now it will be.

Charles McCluskey – Lair 515

Also remembered: Hugh Sharp – Lair 169

We were recently contacted by Dean, who asked if his wife Maria could visit the cemetery after they discovered that her great-grandfather, Charles McCluskey, was buried at Hartwood. Like many of the families who reach out to us, they had grown up hearing fragments of conversations—snippets whispered between adults, not meant for young ears, but remembered nonetheless. As time passes, the meaning of those words becomes clearer.

As is often the case, the historical records held some inaccuracies—possibly due to poor literacy at the time, a misheard name, or a simple clerical error. Charles was originally believed to have been born in Mid Calder, but thanks to Dean’s research and our own verification, we now know he was born in Cadder near Kirkintilloch, and we’ve confirmed his correct birth date and his wife’s maiden name.

On Thursday, Dean and Maria visited Hartwood, where we were able to pinpoint Charles’s final resting place. They planted a ranunculus in a pot near his lair and placed small butterfly decorations around it—a quiet, heartfelt tribute. Like so many visitors before them, the realisation settled in that they were probably the first family members to visit his grave in over a century.

It’s important to acknowledge the historical context. Mental health was rarely understood, and stigma ran deep. Families often didn’t know how to cope or talk about loved ones who were admitted to asylums. For many, silence seemed easier than heartbreak. But that silence didn’t mean those lives weren’t deeply felt or loved.

Dean expressed something that resonates with many:

“I do think we are lucky to find him, as many of my family ended up in common ground or paupers' graves and their exact location cannot be pinpointed. I found it surprising and comforting that the people at Hartwood took the time to number the graves and keep such detailed records.”

But their journey didn’t end there.

Dean’s continued research uncovered even more of the family’s hidden story. He found that Charles had a cousin, Hugh Sharp, who is buried in Lair 169. Hugh died a year before Charles, on 1st May 1911. He was born on 12th December 1872 in Cadder, the son of Patrick Sharp and Jane Gallacher.

Dean also discovered that Charles’s brother Edward had also been a resident at Hartwood. Edward self-admitted and was always considered “sane.” Later, Edward’s fourteen-year-old son was nearly admitted after intervention by the Tollcross Police, but was ultimately refused.

This has sparked a new line of thought for us: just how many cousins, siblings, and family connections lie quietly among the 1,255 graves at Hartwood?

Rest in peace, Charles and Hugh.

You are remembered, not just in names or numbers, but in stories finally being told.

Roseanne McIver Lowe Lair

Also known as Rose Ann McKeever, McKever, McIver or Low

Admitted to Hartwood Asylum in 1910

As Told By Janice McCrossan

Roseanne’s life was marked by hardship, loss, and strength in the face of unimaginable sorrow.

She married William Lowe in 1888 in Saltcoats, Ayrshire, and together they raised six sons: Robert, James, William, Thomas, Charles, and Michael.

Like so many mothers of her generation, Roseanne watched her family torn apart by war. Her sons answered the call to serve during the First World War, and the toll it took on her was immense. Two of her sons—Thomas and Charles—never came home. Her son William served in the Navy, while the rest of the family endured the daily uncertainty of wartime.

In 1910, just before the war began, Roseanne was admitted to Hartwood Asylum. Whether due to personal trauma, mental illness, or the growing strain of life’s burdens, her admission marked a turning point. We may never fully know her struggles, but we do know that grief, loss, and separation from her children likely weighed heavily on her.

In Honour of Her Sons

Private Charles Lowe

Service No. S/4126

9th Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)

Killed in action: 25 September 1915

Commemorated at: Loos Memorial, France

Panel: 78 to 83

Private Thomas Lowe

Service No. S/10484

1st Battalion, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)

Killed in action: 18 November 1917

Commemorated at: Tyne Cot Memorial, Belgium

Panel: 94 to 96

Roseanne’s story is not just one of sadness—it is a reflection of the thousands of women whose silent suffering echoed through generations. Her name, along with those of her sons, now lives on through remembrance, love, and a commitment never to forget those who bore the cost of war in silence.

Rest in peace, Roseanne, Charles, and Thomas. You are remembered.

Jane Muir Symington Lair 203

Shared by her great-grandson, John

One of the most meaningful parts of our work is helping people reconnect with their ancestors—bringing stories long hidden in the shadows back into the light. Earlier today, I received a message from John, who had been searching for his great-grandmother, Jane Muir Symington. He believed she had died at Hartwood Asylum on 22 March 1914, but did not know where she was buried.

He had visited the cemetery around two years ago, unsure of her plot number. After a quick search, we were able to locate her final resting place—Lair 203, in Hartwood Cemetery.

John shared:

“Her name was Jane Muir Symington—though she was sometimes known as Jean or Jeanie. She has an interesting, if tragic, back story.

She was a single mother in 1888, at a time when that was socially unacceptable. I suspect this contributed to her being in Hartwood. She had been there from as early as 1901—very sad, really.

My mother was 93 when she first told me the story. When she was 14, her Granny sent her alone on a train to Allanton every week, carrying a white bowl of food because her mother didn’t like hospital meals. From there, she walked to the clock tower at Hartwood, where her mum was a voluntary patient for what they called ‘her nerves.’

I tried to find out more about my gran and the shock treatment she received. That’s when I discovered that my great-grandfather—her dad—had also spent most of his life in Hartwood with what was called ‘Religious Mania.’ He was buried there too.

We were told he had ‘just left.’ No one ever mentioned his name. But I found him: Edward Murphy, admitted in 1911 and died in 1939. He never left Hartwood.

It was devastating reading about him in the big leather ‘lunatic asylum book’ at the Heritage Centre in Motherwell. But now, he is remembered. It described him as ‘an agreeable, pleasant fellow.’ He wasn’t allowed out because he constantly asked to go home. They saw him as an ‘escape risk.’

He and my great-grandmother married at 16 and had one child, my gran. I have no photo of Edward. But yesterday, my daughter and I visited his grave. He finally had visitors. We brought rocks and shells from beaches around Scotland—places he never got to see.”

Jane’s life was, for many years, forgotten—her memory quietly erased by her family. But John has made it his mission to restore her name, her story, and her dignity.

Jane Muir Symington was born in Lesmahagow in 1865, the daughter of shoemaker John Symington and Janet Forrest. Her parents were married that same year, but by the 1871 census—when Jane was only six—she was no longer living with them. Instead, she was raised by her maternal grandfather, Samuel Forrest, and his family. Throughout her youth, she adopted their surname and was often recorded as a Forrest.

On 14 October 1888, at the age of 22, Jane gave birth to a daughter, Janet Forrest Symington, in Abbeygreen, Lesmahagow. No father was named on the birth certificate. However, a court decree a year later identified Andrew Brown, a labourer from Stockbriggs Farm, as the father. He vanishes from the records shortly afterward.

By 1891, Jane and her young daughter were still living with the now elderly Samuel Forrest. Life continued, marked by hardship.

In 1895, the Lanark District Asylum at Hartwood opened. By 1901, Jane—then 36 and listed as a former domestic servant—was recorded as a patient there. She died at Hartwood on 22 March 1914, aged 50. Her address was listed as Auchterteare Lodge, Lesmahagow, though it’s unclear when she last lived there. Her cause of death was recorded as Morbus Cordis (unknown) and certified by Dr Dunlop Robertson and an attendant named Haggart. Strangely, another woman died just three days later with the same diagnosis, certified by the same doctor and attendant.

Jane was buried in an unmarked grave, Lair 203, in Hartwood’s cemetery. Whether she remained in the asylum for the full 13 years, or if she was ever discharged and later re-admitted, remains unclear.

What Became of Her Daughter, Janet?

Jane’s daughter, Janet Forrest Symington, was raised by her grandfather—or possibly great-grandfather—as the records vary. By 1908, Janet was working as a machinist and married William Shearer, a coal miner from Hamilton. On her marriage record, she declared that “Forrest” was the name she had borne since childhood—"being the name of my grandmother."

In 1913, Janet and William had a daughter, Peggy Shearer. But tragedy struck again when, in November 1916, William was reported missing and later presumed killed during the Battle of the Somme.

In 1922, Janet remarried, this time to Alexander Barr—John’s grandfather. She used both surnames: calling herself Janet Symington, but signing the marriage certificate as Janet Shearer.

This story reminds us just how easily society once erased people—especially women—who didn’t fit the mould. But names like Jane Muir Symington matter. Her story, once buried and forgotten, now lives on thanks to the love and dedication of her great-grandson.

We are honoured to help paint a fuller picture of those buried at Hartwood. With each rediscovered life, we return dignity and identity to the 1,255 souls laid to rest here—and help their descendants reconnect with their past.

Rest in peace, Jane. You are no longer forgotten.

Agnes Wilson Lair 117

From Number to Life

One of the most meaningful parts of our work is helping families reconnect with lost ancestors—especially those whose lives were once reduced to a number on a register. There’s nothing more rewarding than being able to say, “We’ve found them.”

In September, we were contacted by Gordon Mason, who was searching for his great-great-grandmother:

“I wonder if this lady is on your list of burials at Hartwood. This is my GG Grandmother. I've never been able to track down her grave, although the family by that point were spread across Lanarkshire and may possibly have taken her for burial closer to one of the various homes.”

After a quick check of our records, we found her: Agnes Wilson, buried in Lair 117. And with that, her story began to unfold.

Agnes had long been something of an enigma in Gordon’s family history. There were many unanswered questions—chief among them, the mysterious absence of any solid record of her alleged husband, William Wilson, ever living with the family.

Agnes first appears in the 1860s in Kirkmuirhill, Lanarkshire, having arrived from Ireland with her sister and children. She worked as a strawberry pollinator, and the children originally bore the surname McCurfill, despite Agnes identifying herself in records as the wife of William Wilson. It was not uncommon for Irish immigrants to adopt the surname Wilsonin Lanarkshire, making Agnes and William Wilson among the most difficult names to trace in the region.

Her sister and daughter later worked as house servants at Crag Lodge in Carmunnock, which was given as Agnes's home address—suggesting they may have cared for her there before she was admitted to Woodilee Asylum.

A particularly moving part of the story involves Agnes’s sister, Mary Ann, who also experienced mental health challenges. She was diagnosed with arteriosclerotic dementia but remained in a family setting, cared for by Agnes’s son, James, in his Stonehouse home, where she died a few years later. Mary Ann was laid to rest in Stonehouse Cemetery.

This contrast highlights how families often made impossible decisions: Mary Ann’s condition may have been more manageable at home, while Agnes’s may have necessitated institutional care—an all-too-common reality at the time.

Records show some inconsistencies regarding Agnes’s age. The 1861 Census lists her as 31 years old, though this varies slightly in later documents. If the 1861 figure is accurate, she would have been around 76 years old when she died on 12 October 1906. She was buried five days later, on 17 October, in Lair 117.

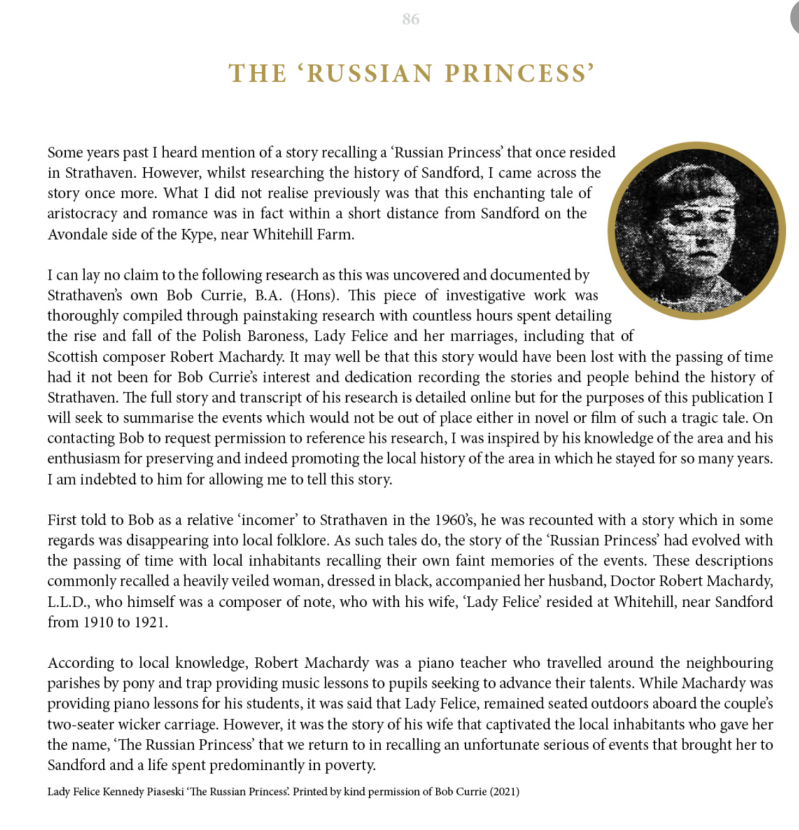

She rests with Elizabeth White (née Craig)—and while we have no formal layout for the cemetery, the lair number places her toward the top back corner, not far from where Princess Felice is believed to rest.

Thanks to Gordon’s persistence and our shared records, Agnes is no longer just a name on a register. Her story—once fragmented and uncertain—is now part of the rich tapestry of lives remembered at Hartwood.

Agnes Carmichael Wilson Lair 117

Agnes Carmichael Wilson was born around 1830 in County Derry, Ireland, the daughter of James Wilson and Jane King. She married William Wilson, though intriguingly, she appears in the 1861 census at Boghead near Kirkmuirhill without him. Living with Agnes were her three young children—Mary (4), Robert (3), and James (1)—all born in Ireland, indicating the family had only recently arrived in Scotland.

Also residing with them were Agnes’s elder sister Mary Ann and their younger brother James. Agnes worked as a “flowerer,” which involved hand-pollinating strawberry and tomato plants in local greenhouses. Nearby lived her mother, Jane King, with another sister, Jane, and her family.

Agnes’s brother James later married three times and established a large family in Stonehouse.

Agnes and Mary Ann eventually moved to Carmunnock, where they found employment as domestic servants or farm laborers. By 1881, the sisters were still living together, raising Mary’s three daughters—Mary had a son before marrying and having five more children later. When Mary left, the elderly sisters continued to care for her older children. By 1901, only Agnes and Mary Ann remained at home, with a 22-year-old granddaughter, Jane, working locally as a domestic servant.

Mary Ann passed away in 1902 while living with their brother James in Stonehouse; he died a year later in 1903.

In 1904, at the age of 74, Agnes was admitted to hospital, initially Woodilee Asylum, and later died in Hartwood on 12 October 1906. She is buried in Plot 117 alongside Elizabeth White (née Craig). Both Agnes and Mary Ann had arteriosclerosis, which, alongside emphysema, heart failure, and lung congestion, was listed as Agnes’s cause of death.

Agnes’s daughter Mary also died in 1906. Little is known about her sons James and Robert, but many of Mary’s children went on to marry and have families. For example, one granddaughter—my grandmother—had 16 children, almost all of whom married and produced at least 30 grandchildren, along with many great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. Descendants of Agnes Carmichael Wilson are now scattered worldwide, from Australia to the Americas, though many remain in Scotland. It’s estimated that several hundred people worldwide can trace their lineage back to Agnes.

Piecing Together the Final Years

In researching the timeline leading to Agnes’s death, I felt a sense of abandonment surrounding her hospital admission, especially since her death certificate made no mention of next of kin.

In the 1901 census, Agnes and Mary Ann were still living together in Carmunnock, ages recorded as 74 and 78 respectively, both listed as “former farmworkers,” likely reflecting limited or no income. A 22-year-old granddaughter, Jane, lived and worked locally but then disappears from records, possibly due to marriage or emigration. Agnes’s daughter Mary lived with her husband and children in Bridgeton.

By 1902, Mary Ann had died while living with their brother James, who died in 1903. Another sister Jane and their mother, Jane King Wilson, had also died by this time, leaving Mary as Agnes’s nearest kin. However, Mary was battling cancer while caring for her younger children and died only eight days after Agnes.

In an era before the NHS and formal social care, it’s possible that Agnes’s hospitalization provided the family some respite to focus on Mary’s care during her final months, believing Agnes was safe and looked after. The close timing of their deaths suggests a strong emotional connection between the two women.

Mary’s eldest daughter—another Agnes, and my grandmother—was responsible for registering Mary’s death. She gave Mary’s age as 40 (at least eight years younger than her actual age) and listed herself as Mary’s sister rather than daughter, continuing a family tradition of inconsistency in official records.

Notes on Family Records and Agnes

Agnes’s father is listed as James Wilson on census returns (1861, 1881, 1891, and 1901), rather than William as noted on her death certificate. James was the husband of her mother Jane King and the father of her sister and brother, as confirmed by their death certificates.

Based on census data, Agnes was born around 1830, making her approximately 76 years old at her death in 1906.

Hortense Vervoort Lair 289

We recently received a heartfelt message from a relative eager to share their family story. We always encourage this—after all, it’s their story to tell, and no permission is needed from us.

I truly admire the work you do. My 2nd great-grandmother was admitted to Hartwood, resting in Lair 289. Unfortunately, her voice was never truly heard, but I’m grateful for the chance to share her story.

Hortense Vervoort was born Horthansia Vervoort on 23 January 1892 to Joannes Baptista Vervoort and Joanne Maria Mertens. She was the youngest of six siblings. Her father died when she was only seven years old. Hortense grew up on a farm in Antwerp, Belgium. (A photo of Hortense accompanies this story.)

She married Julius Van Megroot on 21 December 1913, and we believe she was happy at first.

When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, Hortense became a Belgian refugee and fled from Antwerp to Glasgow. She arrived in Glasgow in March 1915, seven months pregnant and alone. Julius was a Belgian soldier fighting in France. Hortense had no family in Glasgow and spoke very little English.

She gave birth to a baby boy, Albert, on 9 June 1915.

Shortly after, on 22 June 1915, Hortense was admitted to Renfrew District Asylum. Her diagnosis was recorded as "person of unsound mind." On 6 January 1916, she was transferred to Lanark District Asylum (Hartwood), where she remained until her death on 7 March 1919.

According to her admission notes, she was considered suicidal and dangerous to others, and it was believed she would remain in the asylum indefinitely.

During her stay, Julius never visited her. The only visitors she had were representatives from Belgian charities who offered comfort and financial assistance. It is understood that Hortense suffered from postnatal depression and desperately needed a friend.

Reports noted that she showed little or no interest in her infant, refused nourishment, and was anxious about her husband, who was fighting at the front. There were rumors that Julius was having an affair with a German woman, leading Hortense to believe she had been abandoned.

While at the asylum, Hortense was described as extremely emotional, often crying out and weeping hysterically. Unable to understand her condition, doctors confined her to bed for days at a time, during which she developed several bedsores.

After nearly three years in the asylum, Hortense died on 7 March 1919 from disseminated tuberculosis.

Following her death, Julius and their son Albert—who would have been nearly four years old—emigrated to Canada.

With kind regards,

Charlotte

Rest in peace, Hortense.

Jock O'Law

Robert Yuill Lair 130

Perhaps one of the greatest tragedies of the so-called “golden age” of large public asylums is the countless children who died within their walls. Many children were committed to these institutions, though very few were truly mentally ill.

Children with epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and other conditions were often institutionalized simply to remove them from their families’ care. These children were subjected to the same harsh treatments as adults, including brutal methods such as branding. Due to the security measures and the stigmas of the era, children committed involuntarily were rarely visited by family members, leaving their treatment unchecked and without outside oversight.

Given these bleak circumstances, it is perhaps unsurprising that children experienced unusually high mortality rates in large state-run asylums. Some deaths may have resulted naturally from untreated or poorly managed epilepsy, but one must wonder how many others were caused by abuse, suicide, infections such as malaria, and the myriad other dangers endured in these institutions.

The early 20th-century obsession with eugenics added another horrifying layer to this tragedy. Intellectually disabled children and those deemed “racially impure” were institutionalized as part of society’s cruel attempt to “cleanse” itself of those considered undesirable.

Thankfully, times have changed, but the journey toward acceptance and compassion must continue.

Research by Liz Smullen uncovered the story of Robert Yuill, buried in Lair 130. Robert was institutionalized at age seven. His records noted that while he could do some things for himself, he needed assistance with others. Born out of wedlock in the early 1900s, this may have influenced the path taken for him. He lived in an institution in Larbert before becoming a patient at Hartwood as a teenager. Over the years, his behavior deteriorated until he was described simply as a “clappy, happy, drooling young man.”

One haunting observation noted no change in his condition one day—and the very next day recorded that he had died. No detailed explanation was given for his death at just 26 years old.

It is heartbreaking to imagine that Robert was a lonely, frightened boy, separated from his family by the parish council. The treatments he endured, along with isolation, likely had a devastating impact on him. He was probably among the first patients at Hartwood Hospital, and as a family, we were deeply saddened to learn his story.

We are incredibly grateful to the team who located his grave, and a marker has now been placed in his memory—so that Robert may finally know he is not forgotten.

Our Polish Princess Lair 185

A tale of riches to rags

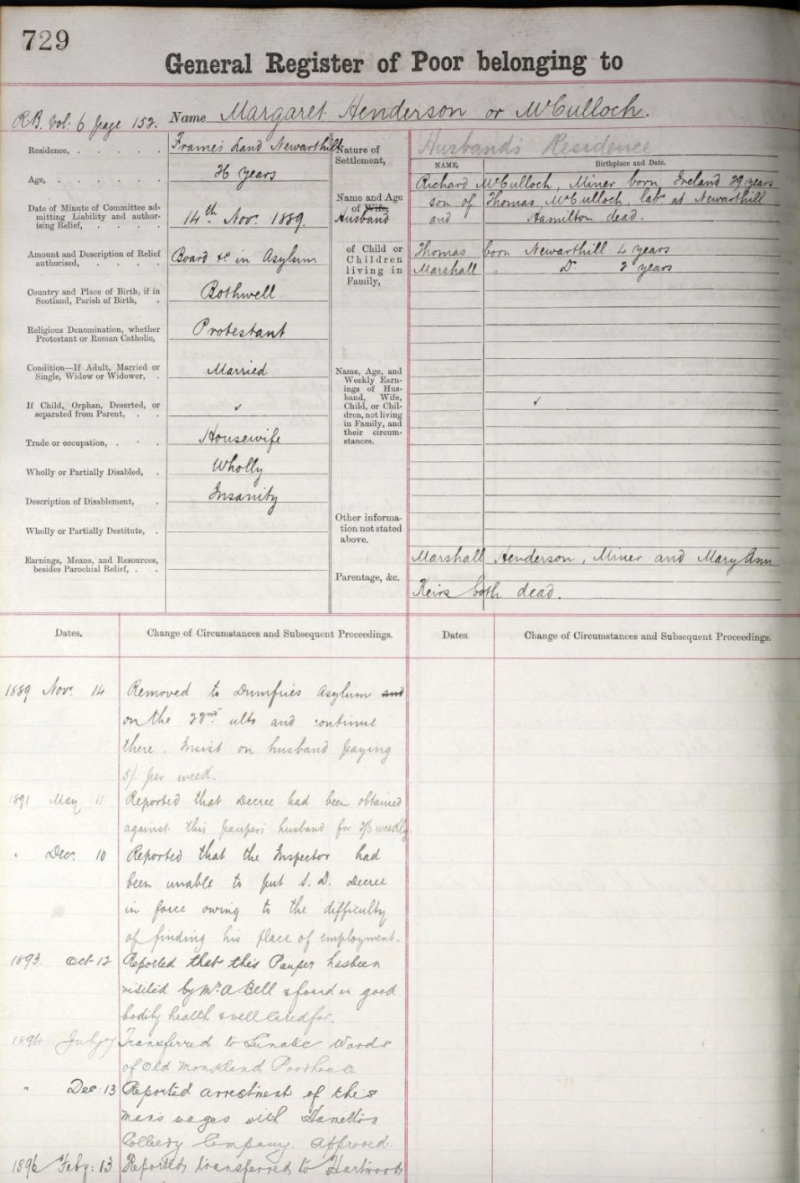

Margaret Henderson McCulloch Lair 74

Another Piece of History Reunited

We were so moved to hear from Steven, who recently discovered that his great-great-grandmother, Margaret Henderson McCulloch is interred within our wee cemetery — resting in lair 74

Margaret was the daughter of Marshall Henderson and Mary Ann Keirs, and her story, like so many others in our care, speaks to a life marked by hardship and strength.

It’s always deeply touching when a family connection is made — when descendants find their roots and a sense of closure, or even pride, in knowing where their ancestors now lie in peace.

This is just another example of how our work at the cemetery continues to bring new meaning and, at times, healing to those searching through the branches of their family tree. A tragic past, perhaps — but with a beautifully poignant ending.

Thank you, Steven, for sharing this with us.

Isabella McDonald Lair 547

I reached out as I found out through “ Find a Grave” that a distant ancestor of mine Isa McDonald is in lair Lair 547.

John McDonald - Andover

Isabella Ferguson or Plenderleith Lair 246

I am hoping that you will be able to tell me if my Great, Great Grandmother, Isabella Ferguson or Plenderleith, is buried in Hartwood Graveyard. Scotlands People’s records (per attachment) shows that she died January 24, 1917 at Hartwood “Asylum” Shotts.

Any information that you can provide would be most appreciated.

Regards,

Heather AlexanderCanada

Theresa Roddis Lair 584

Theresa Roddis Born 2nd April 1891 at 195 Preston Street Bridgeton Glasgow. Parents were James Roddis occupation Tinsmith Journeyman and Isabella Roddis maiden surname McDonald Housewife.

Theresa had two Siblings: James Roddis born 1893 & Charles Duncan Roddis born 1895

In 1918 Teresa was residing in 61 Granville Street with her parents. Her brothers were listed at this address but both serving in the Forces.

Teresa was admitted to Hartwood Asylum Date unknown occupation Postal Clerkess & Telegraphist, Marital status single. Usual residence 61 Granville Street Glasgow. She died in Hartwood Asylum on the 7th of April 1946 @ 12 noon age 55 years. Her parents were both deceased.

Teresa was laid to rest in Lair 584 alongside Lily Ewing.

Lily was born 4th April 1900 at 70 Omoa Square West Dist. Of Shotts. Her Parents were John Ewing occupation Steelworker & Marion Ewing maiden Surname Paton, Housewife. Lily had 5 older siblings: Agnes born 1888, Alexander1891, Annie 1893, William 1896, John 1896.

Date of Admission Unknown her usual address was Motherwell. Marital Status Single. Lily died in Hartwood Asylum @ 0:10 pm on March 22nd, 1946, age 45 years.

Isabella Brown

To The Hartwood Paupers Cemetery Group: Attached are some documents of my Grandfather’s Younger Sister, Isabella Brown. Her Birth Cert. Death Cert. and Death Record. My Grandfather was James Wilson Brown Born Airdrie Rawyards March 1877, died here in Edmonton Alberta Canada, May 1962. Aunty Isabella passed away @ Hartwood Hospital 04 Sept. 1909. This is my connection to Hartwood Hospital. I have blocked out Addresses for Privacy and Security. Please use for your History Archives and Galleries. Enjoy!

Regards,

Norman Brown

Edward Murphy Lair 508

Veronica visited the cemetery to find her maternal great grandfather Edward Murphy,

Edward Murphy was admitted to Hartwood in 1911, where he remained for most of his adult life for ‘religious mania’ before being buried within the cemetery.

Veronica says that she was shocked as the family were unaware that he had been in Hartwood and that he was even buried within the cemetery until last year when her mother told of her visits to Hartwood with food for another family member, where they ‘tied’ up the family connection from our research.

Sadly, Veronica mum said that Edward asked everyday if he could go home, right up until he died.

RIP Edward Murphy, no longer forgotten

Charles McCluskey

We were contacted by Dean asking if his wife could visit the cemetery as they had discovered her great grandfather Charles McCluskey was buried there

Like many stories we hear, living relatives remember hearing snippets, conversations that weren’t for young ears but conversations that remain with us for a reason we don’t understand until we are older.

As we have found with many of the records there is incorrect entries within the historical records. This may have been due to spelling, where family member provided the information as literacy may have been poor or simply due to clerical error.

Charles was no exception. We have now found out he was born in the Cadder area near Kirkintilloch and not Mid Calder along with his correct date of birth and his wife’s maiden name.

On Thursday Dean and Maria came along after we pinpointed Charles to his final resting place.

Dean and Maria have planted a ranunkel in the pot closest to him and left some small butterflies surrounding it.

Like many who visit for the first time, the realisation and often sadness sinks in that they are probably the first relatives to have visited their family member in over 100 years.

What we need to remember was that often families didn’t know how to cope with mental health, that stigma surrounded MH and still does to some extent, so it was often easier to ‘forgot’ them than to be heartbroken about a loved one being placed into an asylum.

‘I do think we are lucky to find him as many of my family ended up in common ground or paupers graves and their exact location cannot be pinpointed within the cemeteries. I found that part most surprising that the people at Hartwood took the time to number the graves and keep a detailed record’

Agnes Morton

I'm working on my family tree, and lo and behold, did I not go and find a relative today who died in Hartwood!! Her name was Agnes Morton, married name Adams and she was born in 1845 and died in Hartwood on March 30th, 1912.

The only information I have about her birthplace is "Midlothian", but I'm not sure if that's right. A lot of my family came from Fauldhouse and birthplaces are shown as Breich or West Calder. I believe that must have been the registration office at the time, but it's often cited as being in Midlothian - maybe that was the case at the time - but both are in West Lothian now.

I've found her on the Find My Past site which doesn't show me how we're related, but it's on my mother's side - that's about all I know for now. And I could find out the relationship if I had her on My Heritage, but I haven't got that far back yet.

I was wondering if you have any information on Agnes in your own records? Thank you xx

Bobbi Jeal

Agnes Wilson Lair 117

In September we were contacted by Gordon Mason, ‘I wonder if this lady was on your list of burials at Hartwood. This is my GG Grandmother. I've never been able to track down her grave, although the family by this point were in a number of locations across Lanarkshire and may possibly have taken her for burial closer to one of the various homes’

With a quick search, we found her on the cemetery list and here her story unfolded.

Agnes Wilson was a bit of an enigma in the family records. and Gordon never found any record of her alleged husband William actually living with the family. Agnes appeared in Kirkmuirhill with kids and her sister c1860 having come over from Ireland. Worked as a 'Strawberry pollinator' and the kids initially had the surname 'McCurfill' despite Agnes listing herself as the wife of William Wilson.

A lot of the Lanarkshire Wilsons were Irish immigrants who changed their names to Wilson, and William and Agnes Wilson are two of the most common names in Lanarkshire. Her Sister and Daughter were house servants at Crag Lodge in Carmunnock, hence the home address, I imagine they looked after her there before she was taken to Woodilee.

A curiosity is that her sister Mary Ann had Arteriosclerotic dementia, and was cared for by Agnes' son James in his home in Stonehouse, where she died a few years later. She's buried in Stonehouse. I can only imagine that Agnes’ behaviour differed and that Mary Ann was more manageable to remain in the cottage, whereas Agnes was institutionalised.

There seems to be uncertainly regarding her age, through the different census's. In the 1861 ceusus she was 31 and in later ones it varied a wee bit. If 31 is correct, she'd have been 76 when she died.

Agnes rests in plot 117, records tell us she died on 12/10/1906 and was buried on 17/10/1906. She rests with an Elizabeth White nee Craig.

As we have no record of the layout of the actual cemetery, we can only go with lair numbers we have found, which would place Agnes in the top back corner near to where the Princess Felice rests.

John Watson Lair 501

I recently learned that my GG Granfather is buried here. His name was John Watson and I believe his plot number is 501.

We have been searching for his death record for so many years and just recently found it. This has been a family mystery for many, many years!

Emily Watson

Augustus Laurel Oliphant Lair 235

Augustus Laurel Oliphant

Born 11th February 1859 Bloomsbury, London, England.

Baptism 31st March 1859 in the Parish of St Giles in the field, Middlesex.

Parents Ferrand Augustus Oliphant Army Contractor & Mary A Elkington.

Augustus had five siblings:

Ellen Harriet Oliphant born 1858 Pancreas, London.

Samuel Oliphant born 1860 London.

Edith Helen Oliphant born 1861 Kensington, London.

Charles Campbell Oliphant born 1864 Middlesex, London.

Herbert Colin Oliphant born 1867 England.

The 1881 Census Shows Augustus living at 2 Mansion Street Camberwell, Lambeth, London with his mother and his sister Edith Helen. A visitor is recorded on the return one Chas. Wells visitor 48-year-old musician (violin) from Soho.

Augustus married Emily Kate Longley on the 29th of January 1887, Holy Trinity, Stroud Green, England. They had two children:

Doris Mary Oliphant Born 12th September 1889, Streatham, Surrey, England.

Eric Ferrand Oliphant Born 2nd October 1891, Streatham, Surrey, England.

The 1891 Census shows Augustus (Insurance Manager) living in Streatham with his Wife, Daughter, two servants & a nurse maid.

Augustus was admitted to Hartwood Asylum as a Private Lunatic in 1900

He died in Hartwood at 1;20 pm on March 10th, 1902, & was buried on the 13th of March 1902. In Lair 235 Hartwood Cemetery. His usual place of residence was The Heugh Bothwell.

Probate: Oliphant Augustus Laurel of the Lanark District Asylum Hartwood N.B .died 10th March 1902. Administration London 3rd April to Emily Oliphant widow Effects £915

Catherine Crerar Lair

It is nice to think that in all probability, Darren’s grandfather John and his brother Daniel (Catherine’s sons) put the headstone at Hartwood, as her husband Daniel died in 1946.I believe Catherine found some contentment in her situation and think she would have been very proud of her sons and all the following generations.Imagining the grave with the snowdrops blooming as you say sounds very comforting and lovely.If you get a chance a photo would be much appreciated to share with the family, namely my father-in-law Donald (Catherine’s grandson).

My research thus far has not ventured too much into Catherine’s family per se. But of course my curiosity is piqued.The basic circumstances of life over the past few years have hindered delving much more into all things ancestry.

However, on our remarkable journey back in 2018, we made many amazing finds and lots of photos.For one, we were drawn to stay in accommodation which we found to actually be really nearby most of Catherine & Daniel’s homes.All are still lived in. And we were made very welcome by all the residents when we visited.

Westsidewood where Catherine was born and where the family worked and lived is a very stately home.Then Cleugh Farm at Wilsontown now with The Bothy as a B & B.And Catherine’s last real home Newmains Cottage, which actually is still very much as it was back then but with some additions. (Newmains House/Farm is just ruins)Newmains Cottage though is now named Dippoolbank.In the past the gardens have often been part of the Scottish Open Garden scheme as you can see from the attached link.

https://www.whatsonlanarkshire.co.uk/event/104406-scotland’s-gardens-scheme-open-garden:-dippoolbank-cottage/

Perhaps we can aim to purchase something from Dippoolbank to contribute to the gardens at Hartwood when we are able to come to the UK again.

When we read through the patient record books at Motherwell it was very emotional. They were quite detailed at the beginning from her admission and slowly over the years writings became less and less.We feel for all involved in the mental health field and the patients, then and now. Many amazing people giving so much of themselves to help others in not simple circumstances.On reading we understood it to be that Catherine did not go back home at any time. But with the infrequent documentation during the years of both of the Wars, we wondered.Mainly with that the eldest son, Daniel, had put his next of kin as his mother, so Catherine of Newmains Cottage, on his WW1 application in 1916.Sadly, Motherwell was not able to find the last few records for Catherine prior to her death.

It is important to talk freely and be open about our past and share the knowledge to understand and begin the healing where it is needed.

Kind Regards,Cathy & Darren Crerar Victoria Australia